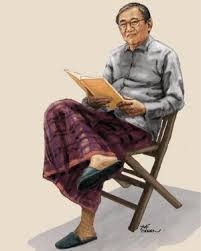

Nurcholish Madjid (affectionately known as Cak Nur) is one of Indonesia’s leading public intellectual and a respected Islamic scholar and reformist. On 30.08.20, The Reading Group collaborated in an online discussion called “Agama Kemanusiaan Pasca Nurcholish Madjid” (Humanistic Religion Post-Nurcholish Madjid), with three other institutions who are at the forefront of keeping his legacy alive: the Nurcholish Madjid Society, Jakarta; Centre for the Study of Religion and Culture (CSRC), Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University, Jakarta; and the Centre for Pesantren Studies, Bogor.

Nurcholish Madjid (affectionately known as Cak Nur) is one of Indonesia’s leading public intellectual and a respected Islamic scholar and reformist. On 30.08.20, The Reading Group collaborated in an online discussion called “Agama Kemanusiaan Pasca Nurcholish Madjid” (Humanistic Religion Post-Nurcholish Madjid), with three other institutions who are at the forefront of keeping his legacy alive: the Nurcholish Madjid Society, Jakarta; Centre for the Study of Religion and Culture (CSRC), Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University, Jakarta; and the Centre for Pesantren Studies, Bogor.

The session featured Ahmad Gaus from CSRC; Dr Azhar Ibrahim from the National University of Singapore; and Huda Ramli from Sisters in Islam, Malaysia. Executive Director of Nurcholish Madjid Society, Fachrurozi Majid gave the Keynote Address and Nur Hikmah of The Reading Group moderated the session.

The session focused on Cak Nur’s key message of humanism that flows from his religious philosophy. Fachrurozi, in his Keynote Address spoke of Cak Nur’s main contributions to society and calls for the continuation of his message, particularly that of uplifting the conditions of the marginalised in society through the humanitarian approach.

Ahmad Gaus, who had written extensively on Cak Nur including a biography called ‘Api Islam’ (The Torch of Islam), emphasised the ‘tauhid’ (radical monotheism) of Cak Nur. Cak Nur’s ‘tauhid’ would not admit any form idolatry, including that of power, wealth or the state. This is where Cak Nur’s pluralism stands out: any denial of diversity in order to concentrate and monopolise truth and power, is to imitate God – hence, idolatrous.

There is no doubt that Cak Nur had brought religious thought beyond the ‘traditionalist’ and ‘modernist’ divide in the Malay-Indonesian world, exemplified by two mass-based movements, Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah. Since his clarion call for ‘Pembaruan Pemikiran Islam’ (Renewal of Islamic Thought) in the 1970s, Cak Nur situates his project as that of ‘preserving from the past what is good, and taking from the present what is better’.

There is no doubt that Cak Nur had brought religious thought beyond the ‘traditionalist’ and ‘modernist’ divide in the Malay-Indonesian world, exemplified by two mass-based movements, Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah. Since his clarion call for ‘Pembaruan Pemikiran Islam’ (Renewal of Islamic Thought) in the 1970s, Cak Nur situates his project as that of ‘preserving from the past what is good, and taking from the present what is better’.This project was realised through the formation of Paramadina, an organisation that promotes what Cak Nur calls as ‘masyarakat madani’ (civil society), a term no doubt, derived from his reading of American sociologist, Robert N. Bellah. This term had also inspired the concept of ‘Islam madani’ (civil Islam) that was later promoted by Anwar Ibrahim in Malaysia, although it took a different trajectory under the state-led project of Islamisation.

According to Dr Azhar Ibrahim, whose past postdoctoral research in Copenhagen University drew on Cak Nur’s public theology, the humanist agenda of Cak Nur has yet to be appreciated in its fullness. The humanistic approach is not confined to religious thought but must be realised in other sectors of society, including education. Cak Nur himself, is an educator par excellence, having studied under a leading Islamic scholar and reformist, Professor Fazlur Rahman in Chicago University.

Despite all these, Cak Nur’s reformist views remain controversial within certain segments of society. Huda Ramli, who works for Sisters in Islam in Malaysia, reminds the audience of attempts to discredit Cak Nur’s thought under the amorphous term ‘liberal Islam’. There is currently a standing fatwa against ‘liberal Islam’, which made people afraid to explore views propounded by the likes of Cak Nur. The attacks against ‘liberal Islam’, it was noted, came from within the environment of politicisation of Islam, whose proponents are known as ‘Islamists’.

Hence, it is crucial to first critique the ideas of political Islam before Cak Nur’s humanistic views can take root. It must not escape observers that Cak Nur had anticipated the hardening of political Islam back in the 1970s, hence his call for “Islam, Yes; Islamic Party, No!” – which caused a stir in Indonesian society that reverberated throughout the region, particularly in Malaysia where the ruling party, UMNO was faced with the challenge of the Islamist party, PAS who called for Islam to be the basis of governance.

In the final analysis, whether one agrees or not with Cak Nur’s reformism, he remains as one of the formidable ulama of the contemporary Malay-Indonesian world. His vision for a civil religion – one that is tolerant, compassionate, democratic and open to religious diversity – is suited for a modern world that has to grapple with a multitude of problems in the spheres of politics, economy, education and social relations.

At the end of the day, it is important to remember that Cak Nur’s core approach is to highlight the ‘good of religion’ more than the ‘truth of religion’. No one can disagree on the good that religion brings to human civilisation, but not all can agree on the truth in every religion. The good, therefore, is inclusive and can be a unifying factor; while truth remains subjective, contested and even personal to every individual. The focus on the good is also what makes us human.

Fifteen years after his passing on, Cak Nur’s message remains relevant. In fact, it is more urgent considering that humanity is currently faced with the problems of violent extremism, sectarianism, terrorism and threats to the environment, including the pandemic and global climate change. Cak Nur’s values-based approach to religion and society can be invigorating for those who want to go beyond the current impasse in Islamic thought.

Written by: Mohamed Imran, taken from Facebook: